My newsletter is named after a traditional Jewish blessing upon encountering the majesty of a large body of water: “Blessed are you, our eternal G-d, Ruler of the Universe, who made the great sea.” BTS is a free, monthly publication which shares Jewish and non-Jewish approaches to mindful, contemplative living. Some come from from spiritual teachings from the past and the present; others from my Zen practice and Jewish faith. Included here are also some of my own news as well. BTS is a conversation, and I enjoy hearing from and responding to the readers.

“The Stoney Nakoda First Nation believes everything has a living spirit: humans, wildlife, rocks, water, mountains, insects, everything. Maligne Lake (Chaba Imne) is a very special living entity to them, where the surrounding mountains are physical representations of their ancestors and tiny Spirit Island provides the beating heart for the living lake as well as a venue for Nakoda ceremonies and traditions.”

— National Parks Traveler, 2023

Hiking eight days in the Canadian Rockies was a great way to finish the summer, but it came unexpected.

Having seen my other summer travel plans evaporate, I contacted the organizers of a Sierra Club trip on an off-chance for a last-minute cancellation. As a matter of fact, there was one, for a single male roommate. “I’m your man!” I said.

I’d always wanted to visit this part of North America, and it didn’t disappoint: I found an abundance of natural splendor in the Canadian Rocky Mountains: majestic peaks, deep lakes, shimmering glaciers. And a few interesting things to learn along the way.

It’s not the sky

I learned why the color of the lakes is so impossibly turquoise blue and not at all reflecting the pale sky.

The ice melt water which feeds these lakes brings along the so-called rock flour, a product of friction between the glacier and the rocky ground. Its particles are lighter than water and thus rise to the lake’s surface, covering it with turquoise sheen.

Beauty of micro-landscapes

There is a certain delicacy in the Northern landscape: with a short warm season, the growth of many plants is stunted, making them miniature, with some details so small they are almost invisible to the eye. Plant your feet in one spot and get lost in the micro-landscape of blueberry leaves creeping along the mossy ground, punctuated by mushrooms varying in color from pink to foxy brown to pale gray.

Foraging

To my surprise, I came upon four berries I haven’t seen in decades: wild strawberries, raspberries, blueberries, and – all over the trails – a profusion of juicy black currants.

Their intense, aromatic flavor brought back memories of foraging trips with my mother and sister into the forests surrounding Moscow. Those trips, with a picnic brought along, were more fun than gain – a common summer activity in central Russia, whose climate resembles the Canadian interior.

I got a few of my hiking companions to try out these berries. They thought they were risking their lives, but no one got sick!

Northern safari

Our bus stopped on the side of a mountain highway so we could observe a grizzly bear grazing on the forest shoots.

In other places, we saw an adult moose emerging from the lake and shaking off its giant antlers – a magnificent sight; bald eagles nesting; a wolverine slithering over the rocks… I probably wouldn’t have spotted these wonders, but luckily, our guides and the Métis bus driver were sharp-eyed and knowledgeable.

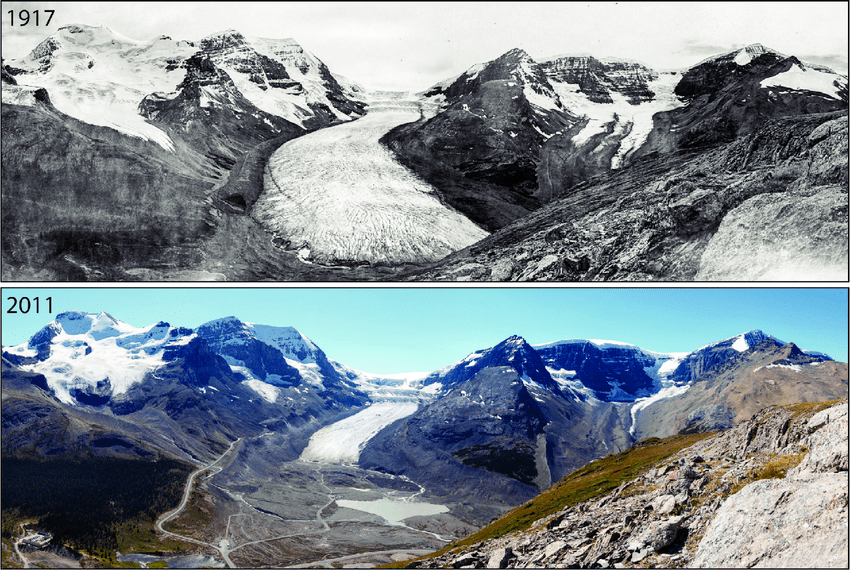

Goodbye, glaciers?

Walking on the Athabasca Glacier, I tasted the icemelt water, which frankly tastes the same as it does in Idyllwild in the early spring.

At the end of the walk though, I felt sad to leave this giant frozen river of ice not knowing if I’ll ever, and I do mean ever, see it again. Scientists predict that due to the warming climate, glaciers like the Athabasca only have 30-80 years left.

How quickly and irreversibly we are destroying our planet! The quickening Anthropocene age is turning it into a post-glacier, post-iceberg, post-frozen North Pole world.

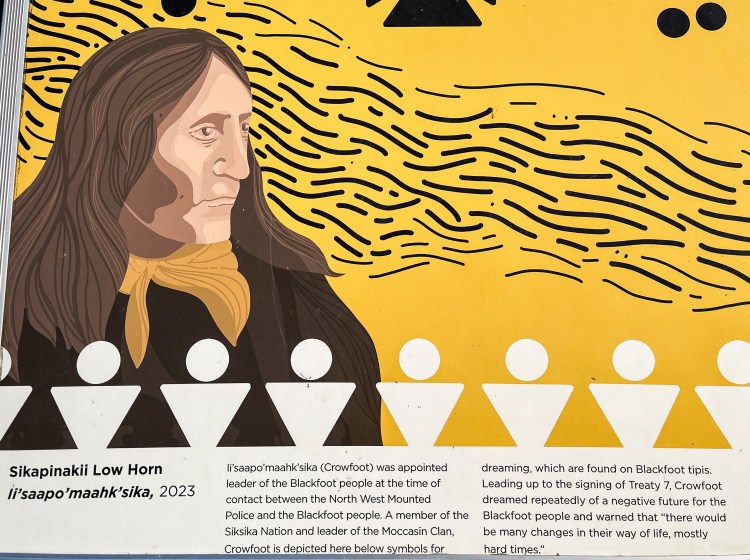

“The Queen wishes to help you to live in the future in some other way…” (From Treaty 7 between Britain and the 6 Nations of southern Alberta)

On the last day of the trip, I took a walk around the Confluence – the site where the predecessor of the city of Calgary, Fort Calgary was founded in 1875. Two rivers, the Bow and the Elbow, merge there, symbolic of the cultures that came here to negotiate their existence in the years to come.

In this drawing displayed at the Confluence, Chief Crowfoot is lost in a cloud of dreams because leading up to the sign of Treaty 7, Crowfoot dreamed repeatedly of a bleak future for his people, predicting “many changes in our way of life, mostly hard times.”

The Blackfoot and the Nakoda saw their livelihood disappear, children placed in boarding schools, and themselves become outcasts, the lowest in the ranks of the empire. The national parks we visited were off-limits to them.

Even today, unlike many parks in the U.S., you won’t hear much about the Native population of the area while visiting Canadian national parks, nor see any visual signs attesting to their historical presence in the area. (Sorry, one slim photo book in a park store about Native peoples next to dozens about everything else is not enough).

As people moved into the region from other parts of Canada and Europe (and now also from Africa, Australia, and the Middle East), Calgary became the oil and gas capital of the country, with its resource-based economy contributing trillions of dollars to the Canadian economy, and the area wealthy and safe, for the most.

How do you move forward?

These historical events can be interpreted in different ways. One is to call for the dismantlement of the colonial state of Canada, which committed cultural genocide upon the Native people of the area, dispossessing them of their land, destroying their way of life, and continuing to discriminate them, the refugees in their own land, for not being White enough.

One can also praise the very same events as an opportunity for the primitive locals to become civilized. Western economy has brilliantly developed and exploited the land’s natural resources, built modern cities and beautifully maintained farms. Western education provided the Native population with a path to success in a technologically advanced, global society, just as Western religion has shown the way to integrate culturally.

A third way is to recognize the complexity of successes and injustices of the past, note them, not just move blindly on, and strive to make more skillful, more inclusive choices moving forward. After all, we all live in the present and not in the past, and the waters of the Bow and the Elbow continue to flow. That would be my preferred choice.

There is also the fourth way, which is to retreat into one’s inner spiritual temple, immerse into the study of one’s own culture which offers so much love and strength, and leave the noise of the savagely unjust human world outside. I do it at times, even if not for too long, when I find it a healthy alternative to being over-engaged. So I keep it on my preferred list as well.

What sustains us

I left this magnificent region with a new word: kitao’wahsinnooni, a Blackfoot word meaning ‘that which sustains us’. It describes a concept of interdependence of home and the environment of which it is part.

There is sustaining power in this relationship. There is a deep reverence in this word.

Kitao’wahsinnooni,

–Lane

Related BTS issues:

#46 A Galilean Notebook, Part 1