“No single event can awaken within us a totally unknown stranger. To live is to be slowly born. A sudden illumination may now and then light up a destiny and impel a man in a new direction. But illumination is vision suddenly granted the spirit, at the end of a long and gradual preparation . . . I should expect nothing of the hazard of war but this slow apprenticeship. Like grammar, it will repay me later.”

Antoine de Saint-Exupery, Flight to Arras (1942)

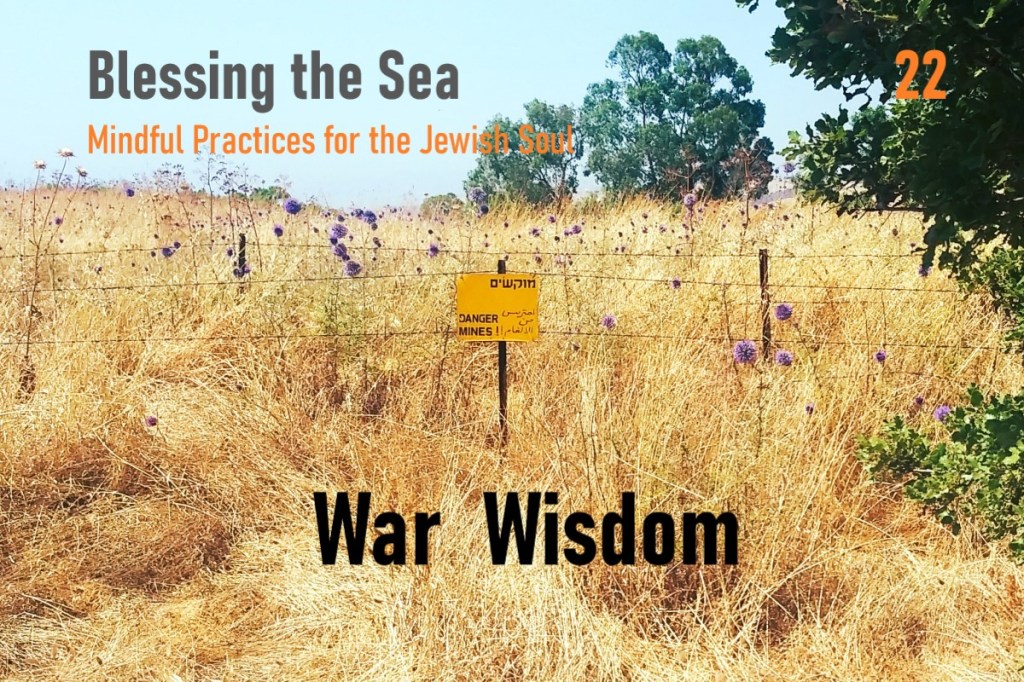

War is destructive, but also transformative, like an earthquake piling up new mountain ridges and transforming the landscape.

It is also deeply insightful. Disrupting the existing social order, settled lives and laws, the thin layer of civilization that we take for granted, it shines the light into the deepest recesses of the human soul. In other words, war contains a wealth of wisdom about human condition.

Leaving aside popular masterpieces like Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front about German soldiers’ experiences in WWI, and Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried based on his tour of duty in Vietnam, I’d like to introduce you to three lesser-known war memoirs I read recently. Like in O’Brien and Remarque, their protagonists enter into the most destructive experience they can possibly imagine, and here they tell us their story, share what they have learned from war about the world and themselves.

Matti Friedman’s Pumpkinflowers: A Soldier’s Story of a Forgotten War (2016) unfolds in the mid-1990s on a hilltop in southern Lebanon in the last years of the Lebanon war. Arriving there, young, inexperienced recruits like Matti are met with a constant threat from the missiles, mines, and snipers, the danger growing more pointless as the pullout is imminent.

There is no combat-style battle, instead, Matti’s buddies are steadily wounded or killed off in brutal and bizarre circumstances. What can one learn from such a harrowing experience?

“Perception of the thinness of line between here and gone,” Friedman writes, “is the debt I owe that place, and the reason I am grateful for my time there. I happened to be lucky on the hill, and so remained convinced of my invincibility, of the impregnable nature of the line.”

“Only now do I understand that it’s just an angle, a moment, a clerk’s stamp on a piece of paper, a step in one direction or another. This belated insight provoked an unexpected feeling [of] retroactive fear. My twin sons are seven and daughter three. Sometimes when I am pushing the little one on the swings in the afternoon and she points the tips of her red sandals at the top of the cypress trees, I know I could have missed this. I almost missed it. Others did.”

Antoine de Saint-Exupery, the author of The Little Prince, was a pioneer aviator, one among a steadily dwindling number of French pilots in WWII who risked their lives trying to thwart the advance of the Nazi troops.

In his Flight to Arras (1942), Saint-Exupery recounts a reconnaissance mission he undertakes over the burning towns and villages of France and streams of refugees fleeing in all directions toward an uncertain end. Every page of this short book is ablaze with meditations on human condition and meaning of life. He won’t come back from his next mission.

“This morning France was a shattered army and a chaotic population. But if in a chaotic population, there is a single consciousness animated by a sense of responsibility, the chaos vanishes. . . I shall not fret about the loam if somewhere in it a seed lies buried. The seed will drain the loam, and the wheat will blaze. He who accedes to contemplation transmutes himself into seed.”

“He who bears in his heart a cathedral to be built is already victorious. He who seeks to become the cathedral’s sexton is already defeated. Victory is the fruit of love. Only love can say what face will emerge from the clay. Only love can guide a man towards that face. Intelligence is only valid when it serves love.”

I came on Siege in the Hills of Hebron (1958) by chance. It’s a rare book, though copies can be found online.

Through personal diaries, community bulletin articles, and interviews, the editor Dov Knohl reconstructs the story of the Etzion bloc of Jewish agricultural settlements established on the Jerusalem-Hebron highway during the Ottoman and Mandate times. Its residents enjoyed peaceful relations with their Arab neighbors, many of whom worked at or otherwise benefitted from the settlement.

After the UN partition of Palestine in 1947, the Etzion villages found themselves cut off from other Jewish areas and continuously attacked by the British-aided troops of the Arab Legion determined to raze them. Mothers and children left Etzion for Jerusalem, but most other villagers stayed. Even though they knew they were doomed, their spirit remained high, resilient. Why?

“Life is continuing here as usual,” recounts one diary entry. “Every day we have public prayers. We have study circles in Talmud, Mishna, Maimonides, and the weekly portion of the Torah. The reading room is looked after carefully, and many residents use it during the day. The general mood is encouraging. The residents are now more composed and reconciled to the tragedy, to the graves down below on the road to the crags. Something binds us with a bitter grief to those who have departed. . .”

“True, the price is high, but those who will live to see the day can hope to live in liberty, in their independent homeland. I do not know if we shall see it but our children will be free citizens of a free country, and for that we are ready to fight. . . We are doing our duty.”

The bloc fell the day before the declaration of Israel’s independence. 240 of its defenders were killed during the 5-month siege. Yet, the story of living with extreme uncertainty for a spiritually fulfilling purpose continues to inspire. There’s always something bigger than us, if we’re only willing to open our eyes and be lifted by it.

Returning to Lebanon after the war ended, Matti Friedman saw that “with no one to tend to the hilltop, nature was taking it back. You would like everything to stop, to acknowledge that the disappearance of human being matters, but of course nothing stops.“

There is a song about that in Hebrew, written by a woman from a kibbutz that lost 11 men in the war of 1973. She repeats the words “but the wheat is growing again,” because she can’t seem to believe that’s possible.“

To me, these lessons, mined from the darkest places, are about affirming this growing wheat, affirming life, affirming peace.

-Lane