My newsletter is named after a traditional Jewish blessing upon encountering the majesty of a large body of water: “Blessed are you, our eternal G-d, Ruler of the Universe, who made the great sea.” BTS is a free, monthly publication which shares Jewish and non-Jewish approaches to mindful, contemplative living. Some come from from spiritual teachings from the past and the present; others from my Zen practice and Jewish faith. Included here are also some of my own news as well. BTS is a conversation, and I enjoy hearing from and responding to the readers.

“Come out, my love, to meet the Bride

and let us greet Shabbat’s inner light.

Come to us in peace, your Husband’s crown,

among song and good cheer

of your faithful and dear.

Come to us, Bride! O come to us, Bride!“

— From the Shabbat hymn “Lecha Dodi” written in Tzfat by Rabbi Solomon Alkabetz, 1540s

(my translation)

The spiritual part of my trip began before I even boarded the plane. Waiting in line at the gate, I was approached by a rabbi in a white shirt, black suit and a matching black hat, his peyot (sidelocks) tucked behind his ears.

“You want to join us for the mincha (afternoon service)?” he asked me in Hebrew tapping his watch.

I nodded and left the line, rolling my carry-on towards a group of men, who were gathering by the terminal’s high windows facing the East.

The group ranged from a Hasid in a black kaftan with a loose belt to a father and a son dressed like they were coming back from a baseball game. The father was reciting the prayers by heart, his son swiping down the prayer app on his phone.

By the time we got to Aleinu, the ticket agents had checked in most passengers, but used to the daily prayer cycle, they waited patiently until we were all ready to depart. The prayers were said; the plane took off.

The maariv (evening) service was on the plane, high above the clouds. The same rabbi went through the aisles, flagging down the heads crowned with kippot (yarmulkas). A dozen of us followed him to the back of the plane to the corner between the porthole window and the cupboards marked ‘Lemons’, ‘Tea’, and ‘Snacks’.

It felt strange, transcendent, to pray watching the dark clouds passing outside the window below the airplane. With no land beneath our feet, as if on a magic carpet, we were flying towards the Holy Land.

I was heading to Tzfat (Safed), the city of mystics, mentioned in the Talmud as one of the five elevated spots in ancient Israel where fires were lit to announce the monthly New Moon celebrations and the annual festivals.

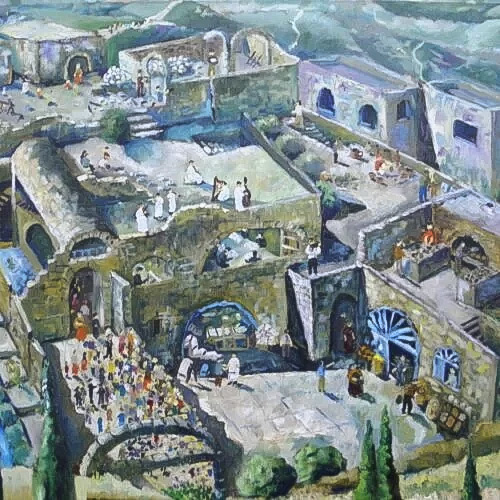

Following the expulsion from Spain, the influx of Sephardic Jews greatly enlarged the already existing Arab-speaking Jewish population of Tzfat.

In 1555, the Ottoman authorities divided the city into 19 quarters: 7 Muslim and 12 Jewish. Each Jewish quarter was named for the place of origin of its inhabitants. Can you guess where they came from? Purtuqal, Kurtubah, Qastiliyah, Musta’rib, Magharibah, Aragun ma’ Qatalan, Majar, Puliah, Qalabriyah, Sibiliyah, Taliyan, and Alaman. (Scroll to the bottom to see the answers.)

The economic success of Tzfat came from the textiles. The convergence of immigrant know-how, abundant Galilean sheep’s wool, and essential waterways for production transformed the city into a major hub for fabric manufacturing and trade.

Many prominent rabbis found their way to Tzfat, among them the Kabbalists Isaac Luria (the Ari), Chaim Vital, and Moses Cordovero. By 1582, there were 32 synagogues registered in the city, as well as an active Hebrew press, the first in West Asia, and for nearly 100 years, Tzfat surpassed Jerusalem as the center of Jewish learning and civilization.

In Tzfat, during its Golden Age, Rabbi Joseph Caro compiled the Shulchan Aruch, the basic manual of Jewish law, used to this day. But Caro also recorded a private, mystical diary of the nocturnal visits of the Maggid, an angelic being who would mentor him here. It was published after his death as Maggid Mesharim.

“Every week, as Shabbat began, the great Kabbalists of Safed would go out to the fields to greet Shabbat in a display of love and honor for this special day. They would joyously recite Psalms, and call out ‘Welcome Bride, Shabbat Queen.’

Around 1540, Rabbi Alkabetz composed “Lecha Dodi,” which became part of Kabbalat Shabbat, the Friday night service, in Safed and the rest of the world. Rabbi Alkabetz died in 1580 and was buried in the old cemetery in Safed, where one can still go and pray by his graveside.” (The Algemeiner, 3/6/25)

I came to Tzfat to volunteer for a week with the non-profit Livnot, which is helping to restore Israel’s war-affected border communities. Our group of 14 volunteers traveled here from the U.S., Canada, and Australia; most were of college age, and some, like me, of the age of their parents.

We would paint, clean out the debris, lay down the tile, and so on. Most work was labor-intensive and dirty, but I found it very enjoyable. It had a lot of meaning, physical exercise, and a lot of spontaneous fun – everything I look for in a volunteering vacation.

Doing this work here in Galilee added a whole other, Kabbalistic meaning. Repairing what is broken here in the Land, we were performing a tikkun, a unification, which, as Rabbi Issac Luria taught and wrote here, helps to reverse the vessels shattered at the beginning of time, lessening of the power of evil, and paving the way of Redemption. In the mystical dimension, every act is important, no matter how miniscule it is.

Most days before volunteering, I would get up at 5:45 to make it to the morning service at the Abuhav Synagogue – a 2-minute walk down the narrow cobblestone lanes. The synagogue, which dates back to the 15th century, is named in honor of the Spanish Kabbalist of the era, Rabbi Isaac Abuhav.

Its design, consequently, is based upon Kabbalah teachings, for example, the bimah (the platform for Torah reading) has six steps representing the six working days of the week; the top level is seventh, representing the Shabbat.

The Abuhav felt warm with festive colors and beautiful decorations. The service was Sephardic, and even though I did not know the melodies, I could follow it easily as the pronunciation is that of modern Hebrew.

The woolen tallit I wore to the Abuhav actually came from a local tallit workshop, which I visited 7 years ago. The synagogue warden would lend me a pair of tefillin, for which I was grateful. At the end of the service, the same warden would bring out a tray with sweet bergamot tea and cookies.

My room in Livnot’s Ottoman house in the Old City: thick walls, low ceiling, and an arched window covered with colored glass.

The Livnot house is older than it looks. Aharon Botzer, the organization’s founder, showed me a large silver coin found under the house. It is dated 1583.

Beneath the house are the tunnels unearthed by Livnot, which contain cisterns for collecting water.

Next to it, there was once a hillside covered with ruins, but after several decades of excavation and restoration by Livnot, the 16th century neighborhood center emerged, complete with a large oven. Called now Beit ha-Kahal, it is designated as a National Heritage Site.

On a weekday night, we made our way through the tunnels to the Beit ha-Kahal as the hail was pounding the doors and windows. In this ancient communal space, we rolled the dough to bake pitas, reliving a century-old experience. People who used the oven would have gone to the same synagogue around the corner as I did earlier that morning. They would have likely left their Shabbat meals in this oven overnight so they wouldn’t have to kindle the fire.

Before we put the pitas in the oven, our trip leader Jamie passed around a small piece of the dough for the hafrashat challah ritual and each of us put into a request. Then Jamie read the blessing from Shulchan Aruch (Ch. 34), written somewhere near this very oven, and set it aside to burn it like a teruma, a Temple offering.

Friday before Shabbat, our group hiked to Nahal Amud at the bottom of the valley to the Hidden Pool of Amud, a lush and wet garden of Eden, with water sipping through and between the moss-laden rocks. The same water that flowed abundantly down the trenches in the cobblestone streets the night before, filling up the cisterns under our house in Tzfat, was now flooding the creeks of Galilee.

There in the ‘Garden of Eden’, we had a bit of eco-Torah study by the creek in the shade of sycamores. We were to pick from the printed guide a tree or a plant that grows in the Land of Israel, and discuss what holy writings say about it, the message these species teach us. The point was to connect their wisdom to our personal life missions.

My study partner and I chose the fig tree. One feature that distinguishes it from other fruit trees, we learned, is that figs do not ripen all at once, but over a matter of weeks. Harvesting figs, like acquiring wisdom, takes time.

Another is that figs are pollinated by female wasps who “in their attempt to brush the pollen [onto fig flowers] lose their wings and other organs. Once the wasp has pollinated a flower and laid eggs, its life ends.”

The booklet then asks, “Would you give up who are today if the world needed you?”

After a full day of volunteering restoring a home in Upper Galilee affected by a missile hit nearby, we returned to Tzfat to meet with the Kabbalistic painter Avraham Loewenthal.

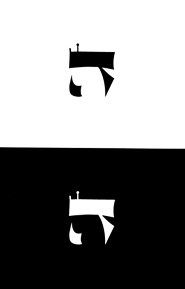

One of Loewenthal’s paintings shows the letter hei (ה) in white against the black background, above another ‘ה’ in black against the white background. (ה) appears twice in G-d’s name. The artist explained that the upper (ה) represents the full, giving love, while the lower (ה) the empty self-love.

Looking at the painting, I sensed the difference. That day, I was giving to others physically and materially, and my soul was in the upper (ה). I felt alive and complete, perfect, the word which in Hebrew is mushlam, that is ‘in Shalom’.

Engaging myself in work that serves others shifted my life into a new dimension—one defined by something far greater than myself.

-Lane

In Part 2 of this notebook, I will focus on my visit to the tomb of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai (Rashbi), the attributed author of the Zohar, the central text of Kabbalah, who was buried on Mount Meron near Tzfat.

* The 12 Jewish neighborhoods of Tzfat: Purtuqal (Portugal), Qurtubah (Cordoba), Qastiliyah (Castille), Musta’rib (local, Arabic-speaking), Magharibah (Magrib, i.e., north Africa), Araghun ma’ Qatalan (Aragon and Catalonia), Majar (Hungary, ‘Magyar’ in Hungarian), Puliah (Apulia in Italy), Qalabriyah (Calabria in Italy), Sibiliyah (Seville), Taliyan (Italian), and Alaman (German).

Related BTS issues:

#42 A Rocky Mountains Notebook

thank you for sharing your experience with Roshi Ryodo and the third hand. What a comforting image.

Warm regards,

Kyoshin

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Lane, for sharing your photos and your poetic response to the beauty of the Canadian Rockies and all that they, and the Native peoples have to share with us. I truly enjoyed reliving our experiences with you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Lane,

Thanks for sharing. I admire your courage, clarity and tenacity. Wishing peace and happiness to you and loved ones. Enjoy your new home and keep writing! Take care.

Deb

LikeLike